Coming Soon to a Workplace Near You: 'Wellness or Else'

By REUTERS

JAN. 13, 2015, 7:09 A.M. E.S.T. - New York Times

NEW YORK — U.S. companies are

increasingly penalizing workers who decline to join "wellness" programs,

embracing an element of President Barack Obama's healthcare law that has raised

questions about fairness in the workplace.

Beginning in 2014, the law known as

Obamacare raised the financial incentives that employers are allowed to offer

workers for participating in workplace wellness programs and achieving results.

The incentives, which big business lobbied for, can be either rewards or

penalties - up to 30 percent of health insurance premiums, deductibles, and

other costs, and even more if the programs target smoking.

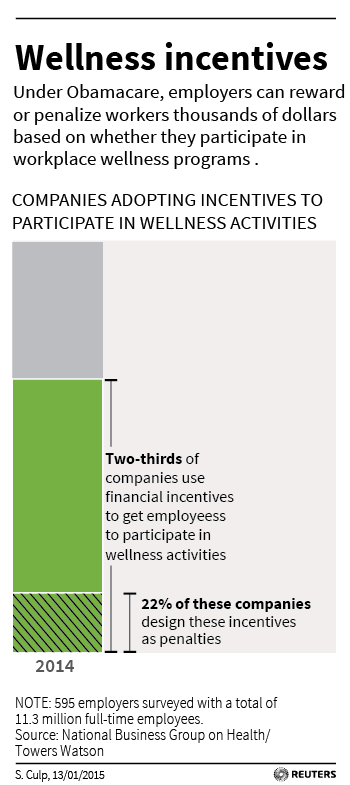

Among the two-thirds of large

companies using such incentives to encourage participation, almost a quarter are

imposing financial penalties on those who opt-out, according to a survey by the

National Business Group on Health and benefits consultant Towers Watson.

For some companies, however, just

signing up for a wellness program isn't enough. They're linking financial

incentives to specific goals such as losing weight, reducing cholesterol, or

keeping blood glucose under control. The number of businesses imposing such

outcomes-based wellness plans is expected to double this year to 46 percent, the

survey found.

"Wellness-or-else is the trend,"

said workplace consultant Jon Robison of Salveo Partners.

Incentives typically take the form

of cash payments or reductions in employee deductibles. Penalties include higher

premiums and lower company contributions for out-of-pocket health costs.

Financial incentives, many

companies say, are critical to encouraging workers to participate in wellness

programs, which executives believe will save money in the long run.

"Employers are carrying a major

burden of healthcare in this country and are trying to do the right thing," said

Stephanie Pronk, a vice president at benefits consultant Aon Hewitt. "They need

to improve employees' health so they can lead productive lives at home and at

work, but also to control their healthcare costs."

But there is almost no evidence

that workplace wellness programs significantly reduce those costs. That's why

the financial penalties are so important to companies, critics and researchers

say. They boost corporate profits by levying fines that outweigh any savings

from wellness programs.

"There seems little question that

you can make wellness programs save money with high enough penalties that

essentially shift more healthcare costs to workers," said health policy expert

Larry Levitt of the Kaiser Family Foundation.

FOUR-FIGURE PENALTIES

At Honeywell International, for

instance, employees who decline company-specified medical screenings pay $500

more a year in premiums and lose out on a company contribution of $250 to $1,500

a year (depending on salary and spousal coverage) to defray out-of-pocket

costs.

Kevin Covert, deputy general

counsel for human resources, acknowledged it was too soon to tell if Honeywell's

wellness and incentive programs reduce medical spending. But it is clear that

the company is benefiting financially from the penalties. Slightly more than 10

percent of the company's U.S. employees, or roughly 5,000, did not participate,

resulting in savings of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Last year, Honeywell was sued over

its wellness program by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. The EEOC

argued that requiring workers to answer personal questions in the health

questionnaire - including if they ever feel depressed and whether they've been

diagnosed with a long list of illnesses - can violate federal law if they

involve disabilities, as these examples do. And, if answering is not

voluntary.

"Financial incentives and

disincentives may make the programs involuntary" and thus illegal, said Chris

Kuczynski, an assistant legal counsel at the EEOC.

Using the same argument, the EEOC

also sued Wisconsin-based Orion Energy Systems, where an employee who declined

to undergo screening by clinic workers the company hired was told she would have

to pay the full $5,000 annual insurance premium.

SICK? PAY MORE.

Some vendors that run workplace

wellness for large employers promote their programs by promising to shift costs

to "higher utilizers" of health care services, according to a recent analysis by

Joann Volk and Sabrina Corlette of Georgetown University Health Policy Institute

- and by making workers "earn" contributions to their healthcare plans that were

once automatic.

Consider Jill, who asked that her

name not be used for fear of retaliation from the company. A few years ago, her

employer, Lockheed Martin, provided hundreds of dollars per year to each worker

to help defray insurance deductibles. Since it implemented its new wellness

program, workers must now earn that contribution by, among other things,

quitting smoking (something non-smokers can't do) and racking up steps on a

company-supplied pedometer.

"Basically, if you don't

participate in these programs, you have to pay something like $1,000 out of

pocket for healthcare before insurance kicks in," said Jill.

Companies insist the penalties are

not intended to be money-makers, but to encourage workers to improve their

health and thereby avoid serious, and expensive, illness.

As evidence of that, said

Honeywell's Covert, the company offers employees "easy ways to get out of" some

of the wellness requirements, such as certifying that they do not smoke rather

than submitting to a blood test.

BALANCING THE WELLNESS BOOKS

Why are companies so keen on such

plans?

Most large employers are

self-insured, meaning they pay medical claims out of revenue. As a result,

wellness penalties also accrue to the bottom line.

About 95 percent of large U.S.

employers offer workplace wellness programs. The programs cost around $100 to

$300 per worker per year, but generally save far less than that in medical

costs. A 2013 analysis by the RAND think tank commissioned by Congress found

that annual healthcare spending for program participants was $25 to $40 lower

than for non-participants over five years.

Yet at most large companies that

impose penalties for not participating in workplace wellness, the amount is $500

or more, according to a 2014 survey by the Kaiser foundation.

"For economic reasons, most

employers would prefer collecting the penalties," said Al Lewis, a

wellness-outcomes consultant and co-author of the 2014 book "Surviving Workplace

Wellness."

Lori, for instance,

an employee at Pittsburgh-based health insurer Highmark, is paying $4,200 a year

more for her family benefits because she declined to answer a health

questionnaire or submit to company-run screenings for smoking, blood glucose,

cholesterol, and blood pressure. She is concerned about the privacy of the

online questionnaire, she said, and resents being told by her employer how to

stay healthy.

Highmark vice president Anna

Silberman, though, doesn't see it that way. She said the premium reductions that

participants get "are a very powerful incentive for driving behavior," and that

"people deserve to be rewarded for both effort and outcomes."

(This version of the story corrects

name, Lorin Volk, in 16th paragraph, to Joann Volk)

(Reporting by Sharon Begley.

Editor: Michele Gershberg and Hank Gilman)